Spirits In The

Box

by Said

Sadain, Jr.

(first published by FOCUS Philippines, Jan. 7, 1978)

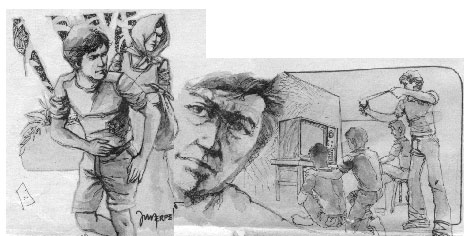

GHAFUR WAS A helpless wreck when the bully Kahal was finally

forced out of the Center by the older people. His eyes hurt and his raw nose could smell

the rusty blood gushing out. His crumpled white shirt was a patchwork of rubber shoe sole

marks, and below the edges of his short pants, his thin knees trembled as if freezing: all

this made him cry in the collective gaze of sympathetic eyes.

Behind the tears, Ghafur thought he saw

his friend, Layla, among the crowd, her young face distorted in disgust but warm in the

reddish light of the setting sun that reached into the room. Then there were more faces.

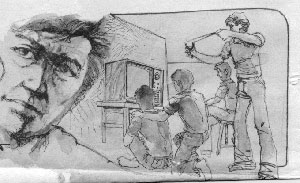

And the blinking brightness of the

sound-and-picture box at one end of the room seemed to glare menacingly.

The brawl between the two boys had been

quick and sudden. When Ghafur was finally persuaded to leave the Center, the crowd settled

back on the long benches and watched the TV show again. The barangay captain who

took charge of the television set from the DPI office in town glanced around the room

apprehensively as if making sure that nothing more would transpire to disrupt the

proceedings. Then he too sat himself in a corner and, like the rest, patiently waited for

the pulong-pulong show to end in anticipation of the promised war picture that

would follow.

From the Center, Ghafur traced his path to

the seashore. He knew that his mother would not approve of his present appearance.

For the third time now as he walked, he

wished upon the stars that should his Kah Abing come down from the mountains, he would

stay with him in Jolo. His Kah Abing could fire an Armalite as easily as a gardener

handles a water hose. And if he does this when and if necessary, then nobody would dare

quarrel with him anymore.

It had just been barely two weeks ago in

their mountain hut when his mother and his Kah Abing had shouted at each other over a

matter which Ghafur’s twelve-year-old sense could not understand. The argument

concerned two things: one, Kah Abing’s refusal to plow the field anymore because of

the dangers brought about by the war and his acquisition of a ‘double body’ from

some friends, and two, of his mother wanting to evacuate him and his brother to Jolo, to

one of the refugee camps there, while the war raged in the mountains.

The argument was not completely settled,

for Kah Abing, his solidly built body bespeaking the firmness of his heart, disappeared

the next day, presumably with the memory of his slain father driving him, and Ghafur and

his mother shortly moved out to Jolo, hurrying through the mountain trails in the manner

of hunted boars.

Jolo herself was not spared by the war.

Ghafur had seen the town in better days when it was more self-composed and livable than

now. The haggard look of abandoned homes and ruble substantiated the suffering glimpsed in

the faces of her residents.

Ghafur and his mother found room in a

bunkhouse at an emergency housing project near the outskirts of town, close by the sea.

The cramped room heated like a boiler when the sun peaked, and froze when the chill sea

breezes blew in the night.

It was very much unlike the comfortable

life they had in their mountain hut – with the air filled by the crying of children,

the shouting of mothers, and by the smoke from the cooking pots boiling atop makeshift

stoves. The older people huddled on the benches lined up under the extended nipa

roofs and the coconut trees, idly talking away the hours while those who ventured into

town did nothing but stand under the acacia trees. A few engaged in whatever meager

business could be started at the marketplaces.

Nowhere was the tranquility of the wild

forest found, except in the more isolated parts of the beach nearby. And in this part of

his new surroundings, Ghafur found his retreat.

Until some few days ago, he had

practically spent his waking hours walking along the white beach, or tanning his skin in

the salty water under an always dazzling sun, or shooting at low-flying birds with his

slingshot carved out of guava wood, or just sitting on coconut stumps and waiting for the

airplanes and helicopters to fly above the sea and over the land. Towards evening, he

would run to the Center and finding himself a seat, he would sit transfixed before the

picture box until all the shows had ended.

It was at the Center that he met Layla, a

hometown friend, she with the dimples in her cheeks. Together, they attended barrio

school, and used to laugh at a teacher who stuttered in speaking a foreign language and

never quite got the lessons across to the pupils. They used to talk about the airplanes

that hovered above the barrio once in a while, about the wheels that rolled under the

rattling machines, and exchanged vague ideas of the cities beyond the sea. And always,

together or apart, they would understand none of these things they talked about.

Then the war came: strange happenings in a

familiar place and people had to move away in search of the familiar things in strange

places.

Ghafur’s bewilderment grew with the

war, with his questions equaled only by his yearning to go home to his Kah Abing. The

picture box, the war, the bully, the suffering – they blended into a confused lot in

his mind.

After leaving the Center, Ghafur soothed

his mind in the evening coolness of the sea. He washed his still painful nose with

seawater and cleansed his face of the hot dust of the Center.

He resented having had to miss the TV

shows tonight. And yet, there was something evil in the ti-bi, he thought, which he

would be better off without. If it were not for it, however, he would not have even gone

to the Center, with its stale smell coming from the sweaty crowd.

But then there was the mystery of the

picture tube. He would not have minded Kahal’s blocking his view of the TV screen,

would not have touched even a bead of sweat on the bare back of the big boy, if that evil

something had not been in the air.

And Layla would not have seen him in such

a ridiculous situation. It hurt even more because Layla had always thought of him highly.

Ghafur blushed in the moonlight. He

stripped his clothes off his lanky body and met the small waves effortlessly, feeling the

coldness as balm.

A moment later, he was skipping back to

the bunkhouse where his mother waited, her deep eyes made deeper by the shadows wrought by

the oil lamp.

Later in the night, sleep was like a wild

bird for the lad, and when finally he caught it, he was immediately carried off on a cloud

of dreams.

The Center is all lit up for the

evening and yet strangely the light from the inside does not permeate the darkness that

engulfs the outside. There is no warmth, not even in the brilliant room, except in the

passion of a presence in the dark: a big man struggles toward the structure.

The man feels the slingshot in the back

pocket of his pants as he stealthily crouches at the doorway. Inside, he could see the

jeering face of the television propped up on a shelf above the heads of the crowd. Its

electronic guttering, the workings of which the crowd never understood at all except as

some sort of a magician’s trick, churned out amplified rasping and emanated a

brightness shadowed by hazy figures.

The crowd laughs when the box laughs, and

cries when it cries. Only the man is detached from the ambience in the Center as he fits a

stone into the crude weapon and stretches the rubber of the slingshot, then stands poised

as if about to confront his prey.

The TV screen meanwhile takes on the

leering face of Kahal, then that of the barangay captain, and when the man in the shadows

finally lets go the stone, the fluid box at the same instant becomes the lovely face of

Layla.

Ghafur woke up protesting the man’s

final act – his timing – but the brightness of dawn engulfed his protest, and

the dream did not seem so painful anymore.

The bilal could be heard intoning

the call to prayer from the nearby mosque – Assalaa-tu khairun minan-naum,

prayer is better than sleep – as the world began to rise in piety.

Quietly, Ghafur’s hands searched for

the slingshot he had slid under his pillow.

LAYLA HAD JUST finished her morning bath by the community well

and her hair was fragrant with the oil from the white meat of the coconut when she saw

Ghafur pass by the bunkhouse.

She called out to him warmly, and the boy,

his head turning everywhere except directly towards her, could not do anything but heed

the call. He went up to her, his mind frantically framing explanations and justifications

for his actions the night before.

He forced a shy smile as he half-expected

sharp words from her, reproaching him as she did once back in the farm when he had

carelessly stumbled in the middle of the road just as a copra truck approached from up the

road.

But there was a different excitement in

her today, something Ghafur had never seen in her before.

"Utuh, have you ever seen

Sambuangan?"

"No – "

"Well, I will be seeing it in a few

days! The big city! My uncle says the city is livelier than Jolo, or the mountains. You

must have seen a city on ti-bi."

"I have, but how are you going to

Sambuangan?" And what about me, Ghafur thought. Aren’t you going to ask why my

eyes hurt or what I think of Kahal?

"My uncle will be taking us there. He

just arrived yesterday afternoon – do you know him? He’s the rich merchant I

used to tell you about. He has this stall in the barter trade market in Sambuangan,"

and Layla gestured with her fragile arms to suggest the size of the place. "He says

he needs my parents to help him with the business."

Layla continued her prattle, mentioning

other things such as schooling, a big house, refreshment parlors, movie theaters and

television sets. But Ghafur had already withdrawn into his inner self, already mourning

something he felt he had irrevocably lost. But as he knew neither what he had lost nor

what was there to be recovered, he desperately surfaced back, wondering how Layla could

talk so fast.

They sat beside the bunkhouse, throwing

pebbles away from them while the girl counted the days to the time she would board a motor

launch for the city. And when finally Ghafur reminded her of the incident at the Center

with a casual "Have you seen Kahal, by the way?", it was as casually dismissed

with a curt rebuke, "Kahal? O, he is too big for you." And the matter was not

mentioned again.

A wind was brewing a giant wave in the

heart of the boy as he left the girl. His feet felt heavy. In the light of Kahal’s

inauspiciousness and Layla’s merriment, Ghafur saw himself sorely beset, and he

attributed all his miseries to the spirits in the picture box.

Towards evening, Ghafur was called by his

mother, who then restricted the boy from going to or even near the Center. In the waning

light of late afternoon, she was still winnowing the new ration of NGA rice as a chunk of mangkuh

flesh sizzled on the embers of a fire built on the ground some distance away from the

long hut.

Ghafur emerged from the bunkhouse and

asked leave to go to the beach for a swim.

"The heat is itching," he said.

"You are not going to watch the ti-bi

again, are you?" his mother asked.

"No."

"Do not even go near it. It is evil.

It is not one with the soul of the mountains."

"Yes."

"It makes people forget their evening

prayers. It poisons."

"Yes."

"And do not cross Kahal’s path.

We are just new in this place."

"Yes."

The mother eyed her son as if looking for

something reassuring in him. What she saw was a young face full of unasked questions.

Soon, she thought, he would have a mind of

his own just like the older one, then he too would find the answers himself, and the face

would be different.

Ghafur did not proceed to the beach

though. He turned a corner and under the growing light of the moon, he headed for the

Center instead.

The cube-like structure, a hastily erected

nipa-and-bamboo building, spacious inside, loomed in dark silhouette against the

ashen sky. The building had served as a health clinic, supply center, seminar room and

schoolroom at other times. The only structure serviced with electricity in the relocation

center, it was dead dark that night.

The barangay captain obviously had

not yet arrived with his kit of electronics.

Ghafur seated himself on the sand off the

road pass in front of the Center. He sat quietly, cradling the slingshot in his palm.

Inside his pockets, he carried the smoothest stones he could find that would fit the small

leather strap of the slingshot.

Several other people were now hovering

around the Center: the older ones in small huddles humming with lively conversation, the

younger ones noisy with their children games. The event of the night before seemed to have

been totally forgotten by all except by Ghafur. And the idea burnt like flame in his mind

as he waited.

When the moon had risen high enough to

light up the town, and it was not certain that the barangay captain was not coming,

Ghafur got up and headed for the beach to bathe.

On the afternoon of the next day, the

picture box was not turned on either. It was explained that something was wrong with it

and that the technician from the DPI office was still fixing it.

The moon meanwhile grew thinner every

night. The Center continued to discharge its other functions aside from that of being a TV

room.

LAYLA HAD ALREADY left the refugee camp and Ghafur’s eyes had

ceased to hurt anymore. He befriended several other kids in the locality and even Kahal

was already on speaking terms with him.

One afternoon, while the local kids played

their usual rough games on the playground beside the Center, the familiar van drove up to

the front of the Center and the barangay captain and his aide were seen trudging

into the building with the picture box in their arms. They were handling it like a newly

born baby.

The children’s games abruptly stopped

and several half-naked kids raced to the Center in glee. Ghafur hesitated – he did

not have his slingshot with him – but at the urging of his friends, he too ran up to

the Center.

The seats were all taken in a short while

and the restless expectations of the crowd tapped off to a hush as the knob was turned to

the only TV channel received in the town.

The shelf, raised majestically five feet

above the floor, with the hunk of electronic contrivance perched upon it, appeared as a

sort of altar graced by a god. The 17-inch table standard, a solid mass in its black coat,

was an alien thing that awkwardly blended with the rawness of the place.

At first, the screen was a dark blur of

horizontal waves, with the funny language belching out of the box. The barangay

captain continued to fiddle with the knobs some more. Then the brightness was diffused by

the heat of unseen forces, and Ghafur’s questions were drowned by a flood of pictures

of a strange city. ###

|